Floating Free: How the Cytoskeleton Changes in Microgravity

Microgravity research is laying the foundations for the future of tissue engineering, organoid formation, and regenerative medicine.

Cells typically grow in flat dishes, spreading out over two dimensions. Living organisms grow in three dimensions to form complex, multicellular structures. When unburdened by gravity, cells organize into three-dimensional clusters that more closely mimic in vivo growth and development (Buken et al., 2019; Grimm et al., 2014).

Beyond advancing stem cell research and therapies for degenerative diseases, these three-dimensional cultures provide more physiologically relevant platforms for drug screening, efficacy testing, and toxicity assessment (NASA, n.d.; Prasad et al., 2020; Fang & Eglen, 2017).

Unlike two-dimensional cultures that often fail to predict clinical outcomes, 3D models better recapitulate tumor architecture, extracellular matrix interactions, and drug resistance mechanisms (Langhans, 2018; Cui et al., 2017).

This predictive capacity addresses a critical bottleneck in drug development, where the success rate from Phase I trials to FDA approval for oncology drugs remains below 4% (Wong et al., 2019).

Additionally, microgravity-derived 3D cultures are extremely useful for studying cellular aging, neurodegeneration, and metabolic disorders in contexts that more faithfully mirror in vivo pathophysiology (Grimm et al., 2014; Costantini et al., 2019).

The Cytoskeleton: A Cell's Response to Gravity

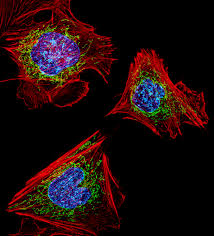

Morphological changes arise from alterations to cellular support structures, particularly microtubules and actin filaments. These bear mechanical loads and detect variations in gravitational force. As loading decreases, their structure and function respond in intriguing ways (Crawford-Young, 2006; Vorselen et al., 2014).

Gravity influences multiple aspects of cellular physiology, including growth, development, intercellular communication, and gene expression patterns. The cytoskeleton is a window into mechanotransduction, how cells convert physical stimuli into biochemical signals (Vorselen et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2004).

Responses are not uniform across cell types. Some exhibit minimal cytoskeletal remodeling even in microgravity. A comprehensive 2014 study conducted aboard the International Space Station examined primary human macrophages, important effector cells of the immune system.

No significant structural changes to key macrophage cytoskeleton components, including actin and vimentin, were found compared to ground controls (Tauber et al., 2017). This heterogeneity in cellular responses suggests that the effects of microgravity depend on cell type, differentiation state, and the mechanical conditions it normally experiences in vivo.

Microtubules: Structure Meets Gravity

Microtubules—hollow, tube-like structures that maintain cell shape and facilitate intracellular transport—are essential parts of the cytoskeleton. While tubulin proteins can self-assemble into microtubules without gravity, the overall spatial organization of the microtubule network depends on it (Papaseit et al., 2000).

Microgravity alters microtubule density, orientation, and dynamic instability, subsequently impacting cell division, motility, and morphology (Tabony & Job, 1992).

The Actin Cytoskeleton: Scaffolding Under Stress

While microtubule networks in microgravity have been extensively investigated for over two decades, what exactly happens to the actin cytoskeleton remains incompletely understood.

The actin cytoskeleton functions as cellular scaffolding, playing an integral role in helping cells sense and respond to mechanical forces. Its role in generating contractile force is pivotal for normal cellular function (Louis et al., 2017; Fletcher & Mullins, 2010).

Microgravity leads to reduced production of actin and related regulatory proteins, including Arp2/3 complex and RhoA. This contributes to the breakdown of the actin cytoskeleton's intricate architecture (Louis et al., 2017; Vassy et al., 2001). When these cytoskeletal processes become disrupted, health issues can arise, from impaired wound healing to immunosuppression.

Understanding changes in the actin cytoskeleton under microgravity conditions expands the toolkit for combatting illnesses rooted in cellular dysregulation and mechanical dysfunction (Maniotis et al., 1997; Ingber, 2006).

Focal Adhesions: Connecting Cells to Their World

Integrins are transmembrane proteins that span the cell membrane. They cluster together to form specialized structures called focal contacts or focal adhesions. These connections link the internal cytoskeleton to its environment, enabling cells to dynamically react to their surroundings (Maniotis et al., 1997; Geiger et al., 2009).

When integrins bind to proteins in the surrounding extracellular matrix, they facilitate the bundling of F-actin (filamentous actin, a structural protein) at sites where the cell adheres to the matrix. This process strengthens focal adhesions and actin stress fibers—tension-generating structures that cells need to attach to surfaces, migrate, and maintain tissue integrity and health (Burridge & Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996).

In microgravity these adhesions do not properly form. They become fewer in number and cover smaller surface areas, mitigating the cell's capacity for adherence, migration, and survival (Bradbury et al., 2020; Corydon et al., 2016). This has implications for understanding how tissues maintain their structural integrity and how cells might function during extended space missions.

Gene Expression and Mechanotransduction

Microgravity also alters the expression of genes involved in focal adhesion assembly and function. Proteins such as FAK (focal adhesion kinase), DOCK1 (dedicator of cytokinesis 1), and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) show decreased expression levels. This impairs cytoskeletal signaling pathways and alters cellular responses to mechanical signals transduced through mechanosensitive ion channels, whether these forces originate from inside or outside stimuli (Bradbury et al., 2020; Versari et al., 2013).

Mechanically Activated Ion Channels: The Next Frontier

Despite continued progress, mechanically activated ion channels in microgravity are largely terra incognita.

These channels—including the Piezo family and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels—convert physical forces into chemical and electrical signals that manage tissue development, wound healing, and vascular tone. Their dysfunction drives an array diseases, from muscular dystrophy to cardiac arrhythmias, yet how altered gravity affects their gating mechanisms and downstream signaling is still be explored (Ranade et al., 2015; Coste et al., 2010; Gottlieb et al., 2008).

Of course, this all goes beyond academic curiosity.

As space agencies plan lunar outposts and missions to Mars, understanding cellular mechanotransduction in reduced gravity becomes essential for health and survival. The cellular behaviors observed in microgravity are opportunities to probe fundamental questions about how mechanical forces shape biology (Herranz et al., 2013).

Simulated microgravity platforms like Litegrav’s PIROUETTE bridge the gap between terrestrial laboratories and orbital research facilities. By making these conditions accessible, they accelerate the pace of discovery while democratizing access to a frontier once reserved for space agencies.

The insights emerging from this convergence of physics, cell biology, and bioengineering will ripple across medicine on Earth and in space.

References and Works Cited

Bradbury, P., Wu, H., Choi, J.U., Rowan, A.E., Zhang, H., Poole, K., Lauko, J., & Chou, J. (2020). Modeling the impact of microgravity at the cellular level: Implications for human disease. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 8, 96. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.00096

Buken, C., Sahana, J., Corydon, T.J., et al. (2019). Morphological and molecular changes in juvenile normal human fibroblasts exposed to simulated microgravity. Scientific Reports, 9, 11882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48378-9

Burridge, K., & Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. (1996). Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 12, 463-519. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463

Corydon, T.J., Kopp, S., Wehland, M., Braun, M., Schütte, A., Mayer, T., et al. (2016). Alterations of the cytoskeleton in human cells in space proved by life-cell imaging. Scientific Reports, 6, 20043. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20043

Coste, B., Mathur, J., Schmidt, M., Earley, T.J., Ranade, S., Petrus, M.J., et al. (2010). Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science, 330(6000), 55-60. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193270

Crawford-Young, S.J. (2006). Effects of microgravity on cell cytoskeleton and embryogenesis. The International Journal of Developmental Biology, 50, 183-191. https://doi.org/10.1387/ijdb.052077sc

Fletcher, D.A., & Mullins, R.D. (2010). Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature, 463(7280), 485-492. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08908

Geiger, B., Spatz, J.P., & Bershadsky, A.D. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 10(1), 21-33. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2593

Grimm, D., Wehland, M., Pietsch, J., Aleshcheva, G., Wise, P., van Loon, J., et al. (2014). Growing tissues in real and simulated microgravity: New methods for tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews, 20(6), 555-566. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0704

Huang, S., Chen, C.S., & Ingber, D.E. (2004). Control of cyclin D1, p27Kip1, and cell cycle progression in human capillary endothelial cells by cell shape and cytoskeletal tension. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 15(11), 5158-5172. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.e04-05-0449

Ingber, D.E. (2006). Cellular mechanotransduction: Putting all the pieces together again. The FASEB Journal, 20(7), 811-827. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.05-5424rev

Louis, F., Bouleftour, W., Rattner, A., et al. (2017). RhoGTPase stimulation is associated with strontium chloride treatment to counter simulated microgravity-induced changes in multipotent cell commitment. npj Microgravity, 3, 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-016-0004-6

Maniotis, A., Chen, C., & Ingber, D. (1997). Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(3), 849-854. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.3.849

NASA. (n.d.). Space cell biology. Retrieved from https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/esdmd/hhp/space-cell-biology/

Papaseit, C., Pochon, N., & Tabony, J. (2000). Microtubule self-organization is gravity-dependent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(15), 8364-8368. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.140029597

Prasad, B., Grimm, D., Strauch, S.M., Erzinger, G.S., Corydon, T.J., Lebert, M., et al. (2020). Influence of microgravity on apoptosis in cells, tissues, and other systems in vivo and in vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(24), 9373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249373

Ranade, S.S., Syeda, R., & Patapoutian, A. (2015). Mechanically activated ion channels. Neuron, 87(6), 1162-1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.032

Tabony, J., & Job, D. (1992). Gravitational symmetry breaking in microtubular dissipative structures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 89(15), 6948-6952. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.15.6948

Tauber, S., Lauber, B.A., Paulsen, K., Layer, L.E., Lehmann, M., Hauschild, S., et al. (2017). Cytoskeletal stability and metabolic alterations in primary human macrophages in long-term microgravity. PLOS ONE, 12(4), e0175599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175599

Vassy, J., Portet, S., Beil, M., Millot, G., Fauvel-Lafève, F., Karniguian, A., et al. (2001). The effect of weightlessness on cytoskeleton architecture and proliferation of human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. The FASEB Journal, 15(6), 1104-1106. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.00-0527fje

Versari, S., Longinotti, G., Barenghi, L., Maier, J.A., & Bradamante, S. (2013). The challenging environment on board the International Space Station affects endothelial cell function by triggering oxidative stress through thioredoxin interacting protein overexpression: The ESA-SPHINX experiment. The FASEB Journal, 27(11), 4466-4475. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-229195

Vorselen, D., Roos, W.H., MacKintosh, F.C., Wuite, G.J.L., & van Loon, J.J.W.A. (2014). The role of the cytoskeleton in sensing changes in gravity by nonspecialized cells. The FASEB Journal, 28(2), 536-547. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-236356