Demystifying Simulated Microgravity

To understand how weightlessness affects life and matter, scientists have conducted hundreds of experiments in space, at costs exceeding $50,000 per kilogram of payload. This has created an urgent demand for more sophisticated ways to simulate microgravity on Earth.

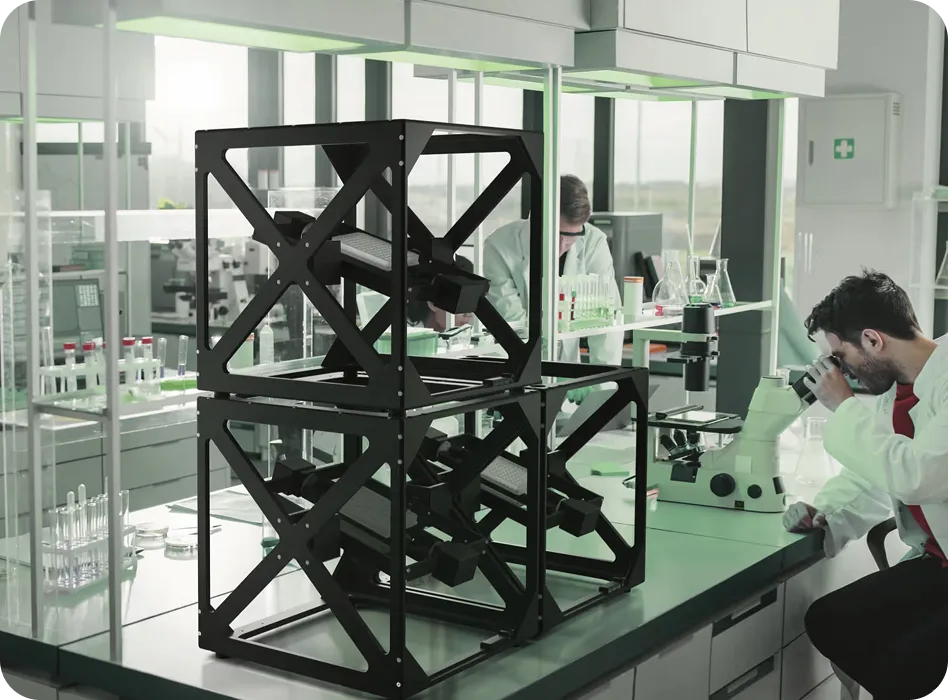

By mimicking off-world conditions, simulated microgravity (sMG) solutions like Litegrav's PIROUETTE are opening new frontiers by bringing extreme environments to terrestrial benchtops. Although it is not yet a household term, sMG already has a rich history and a far-flung literature supporting its use in a vast array of research areas, from microbiology to materials science.

It Begins with a Spin

The clinostat was invented in 1879 by Julius von Sachs to negate gravity's directional pull. By slowly rotating plants around a horizontal axis at rates of about one revolution per minute, these instruments average gravity’s pull over 360 degrees to approximate weightlessness.

Sachs's original clinostat was powered by clockwork, but later versions incorporated electric motors. These devices typically consisted of a vertically-held disc attached to a motor, with plants secured horizontally to the disc. Early clinostats shed light on gravitropism (gravity-influenced growth direction) and gravimorphism (gravity-influenced development)[1].

Clinostats continued to evolve. Contemporary models offer more varied configurations and precise simulations. Modern incarnations include:

One-axis: To study the effects of slow (1–4 rpm) or fast (50–120 rpm) rotations on plant and cell behavior, particularly in gravitropism and cell morphology.

Multi-axis: These feature two or three rotational axes to simulate complex gravitational dynamics.

Random positioning machines (RPMs): Advanced models capable of simulating microgravity by continuously altering the orientation of samples, enabling studies on cellular processes, tissue engineering, and microbial behavior.

RPMs: A Rollicking Review

RPMs descended from the classic clinostat, offering more nuanced and effective ways to nullify gravity.

RPMs consist of two independently rotating frames, with one positioned inside the other. This allows for multidirectional changes in the orientation of the samples mounted in the center.

Unlike Sachs's original clinostat, RPMs achieve microgravity simulation through multi-axis rotation. RPMs advance the concept of "gravity-vector-averaging" by continuously and randomly altering the orientation of samples along two independent axes, effectively reducing gravity's directional pull to (nearly) zero.

RPMs simulate microgravity with greater precision and are suited for experiments requiring dynamic and isotropic conditions, such as tissue engineering or fluid dynamics research. RPMs share a few key features:

Two-axis rotation: Samples rotate around two independent axes, providing a more comprehensive simulation of microgravity compared to single-axis clinostats[2].

Versatility: RPMs can be programmed to generate partial gravity accelerations (~0.1 - 0.9 × g), operate in centrifuge mode, or create specific reproducible paths of sample rotation.

Functional volume: RPMs provide a larger functional volume compared to traditional clinostats, adding scalability and experimental efficiency,

RPMs find extensive applications in scientific research, particularly in studying space-related physiological changes and preparing for missions in outer space[2].

However, it's important to note that the microgravity environment simulated by RPMs is not perfect. Secondary effects, such as shear forces created by fluid dynamics in cell culture media, can have biological implications that must be considered when interpreting results.

Rotating Wall Vessels

Rotating Wall Vessels (RWVs) were a major advancement in microgravity simulation and tissue engineering. Developed by NASA in the 1980s, RWVs were initially designed to provide a sMG environment for cell cultures during non-orbital phases of shuttle missions[3].

These devices suspend cells in a liquid medium rotating on a single horizontal axis, creating a low-shear environment that is ideal for growing three-dimensional cellular structures.

Key features and benefits of RWVs include:

Low-shear environment: The rotary motion counteracts gravitational force, reducing shear stress on cells.

Three-dimensional growth: Cells form tissue-like aggregates and spheroids when cultured in RWVs[3,7].

Versatility: RWVs can be used for various cell types and applications, including cartilage and other difficult-to-generate tissues[7].

RWVs come in two main formats:

- High-aspect rotating vessel (HARV)

- Slow-turning lateral vessel (STLV)

These formats differ primarily in their aeration source.

The microenvironment provided by RWVs allows cells to form aggregates with in vivo-like characteristics, including tight junctions, mucus production, and apical/basal orientation[3]. This makes RWVs particularly valuable for tissue engineering and studying cellular behavior in a more physiologically relevant context.

RWVs have had a significant impact on various fields, including:

- Tissue engineering

- Space biology research

- Drug screening

- Modeling of infectious diseases

While RWVs represent a major step forward in cell culture technology, it's important to note that they still have limitations. For example, the fluid dynamics in RWVs can be challenging, and optimizing operating conditions is crucial for achieving desired results.

Drop Towers and Parabolic Flights

These approaches are worth mentioning, although neither is ideal.

Drop towers provide a few seconds of microgravity while samples are in freefall; parabolic flights extend this window to 20–25 seconds. Although imperfect, these methods have been invaluable for fluid dynamics studies and preliminary biological experiments.

New Horizons

Despite these advances, challenges remained. Shear stress, vibrations, and residual gravitational effects are confounding variables. These have led some to question the direct comparability of sMG to space conditions. Despite these limitations, sMG remains an indispensable tool for reducing costs, increasing accessibility, and facilitating rapid experimental iteration.

As is often the case, the mechanical forces once viewed as constraints have revealed unexpected opportunities. Controlled mechanical stressors have been harnessed to:

- Identify novel biological pathways

- Evaluate drug efficacy in varying mechanical environments

- Generate specialized cell types, like stem cells, with enhanced characteristics

- Optimize bioproduction for improved yields

Altered gravity conditions have been found to suppress tumor cell growth and modify oncogenic signaling pathways, opening new avenues for cancer research.

Precision Engineering: The Next Generation

Microfluidic systems bring precise environmental control to the fold, reducing unwanted shear forces and vibrations[6]. These systems often incorporate biologically relevant contexts, such as embedding samples in organic scaffolds that mimic natural cellular environments.

Automation has transformed the field, enabling high-throughput experimentation. Researchers can now test multiple variables simultaneously, accelerating discovery and ensuring reproducibility.

Litegrav's PIROUETTE platform combines randomized, machine-learning–optimized motion profiles with modular design. PIROUETTE minimizes repetitive patterns and mechanical artifacts that plagued earlier simulators.

Each module operates independently but can be synchronized, supporting up to 12,288 parallel conditions—enabling robust experimentation at a scale previously unattainable.

Conclusion

While not a perfect substitute for spaceflight, programmable microgravity platforms like PIROUETTE demonstrate how automation and precision engineering can overcome old constraints.

By bringing controlled biophysical environments to Earth, Litegrav and similar platforms enable researchers to translate space biology insights into tangible applications—accelerating discovery, improving reproducibility, and demonstrating that gravity is not merely a constant to accept, but a variable to control.

References

- Hoson, T. et al. Evaluation of the three-dimensional clinostat as a simulator of weightlessness. Planta 203, S187–S197 (1997).

- Wuest, S. L. et al. Simulated microgravity: critical review on the use of random positioning machines for mammalian cell culture. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 971474 (2015).

- Hammond, T. G. & Hammond, J. M. Optimized suspension culture: the rotating-wall vessel. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 281, F12–F25 (2001).

- Borst, A. G. & van Loon, J. J. W. A. Technology and developments for the random positioning machine, RPM. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 21, 287–292 (2009).

- Klaus, D. M. Clinostats and bioreactors. Gravit. Space Biol. Bull. 14, 55–64 (2001).

- Kuang, S. et al. Role of microfluidics in accelerating new space missions. Biomicrofluidics 16, 021301 (2022).

- Sanford, G. L. et al. Three-dimensional growth of endothelial cells in the microgravity-based rotating wall vessel bioreactor. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 38, 493–504 (2002).